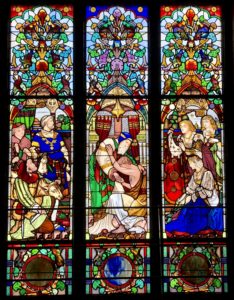

In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This morning we read one of Jesus’ most famous parables, the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32). This is a story near the heart of All Saints’. We have a wall size precious stained glass window of the whole scene in the chapel. It is a powerful story that over the centuries has inspired countless longer versions of spiritual quests of leaving and returning, of being lost and being found, of innocence lost and experience gained. There is, however, a lot more to the parable than that story line. It could be that the parable is really about any of the three characters in the story. Rather than the parable of the prodigal son, it could just as much be known as the story of the resentful, underappreciated, responsible, older brother or even of the parable of the excessively generous father. To understand what Jesus has to teach us requires moving about in the spiritual and mental space created by the parable and to accompany each of the three characters as they bump up against one another.

In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This morning we read one of Jesus’ most famous parables, the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32). This is a story near the heart of All Saints’. We have a wall size precious stained glass window of the whole scene in the chapel. It is a powerful story that over the centuries has inspired countless longer versions of spiritual quests of leaving and returning, of being lost and being found, of innocence lost and experience gained. There is, however, a lot more to the parable than that story line. It could be that the parable is really about any of the three characters in the story. Rather than the parable of the prodigal son, it could just as much be known as the story of the resentful, underappreciated, responsible, older brother or even of the parable of the excessively generous father. To understand what Jesus has to teach us requires moving about in the spiritual and mental space created by the parable and to accompany each of the three characters as they bump up against one another.

We are told of a father who had two sons. The younger son asks to receive his share of the inheritance early. I wonder why? We are not really told that, but we know that no sooner than receiving it, the youngest son hits the open road with his money and what likely appeared to be endless possibilities and novel experiences to be had. Sympathetic readers recognize that young heart full of so many desires and dreams imagining worlds beyond the family farm and hungering for greater satisfactions–like a moth in the darkness fulling the pull of some distant light. This younger brother is far from the only one who has struggled with a human heart searching for what it wants. When the money runs out in some distant country, that son takes a job feeding pigs and is so hungry himself that he envied the pigs the slop they ate. It is then that he starts to reflect on his life in a new way and upon how he could have come so far without finding what he was looking for.

Any act of rebellion, however ill considered, can initially feel like liberation. It can feel like being the very first person to start out on an open road. What is discovered, however, is that with all roads, someone has been there before and even thought that this path is one of the ways other people may travel thereafter. Whatever we may think of our own novel quest, it’s very likely a path that has been travelled in some way before. It is only new to us. The hard-earned truths of experience (such as being so low that you yearn for the food of pigs), can often be learned easier and sooner if we listen to people such as Jesus or any of the other biblical stories that recount human journeys of all sorts and have an uncanny ability to show us where they lead. They may even, like this one, offer solutions to the desires of our hearts more compelling than whatever we may happen to stumble upon, as it were, out on the open road.

The wayward son resolves to return to his father thinking that–whatever apology would be necessary–he would at least be better off working for his father as a hired hand even while he had discredited himself as a son and knowing that there would be no more inheritance to be had. The first hearers of this parable likely wondered whether that was even an option. Why would he even think that he would be welcomed back after what he did? Wouldn’t the father be too angry? Even if the father required the son to pay back what he had squandered, he never could. The son had plenty of time to contemplate what he might be facing as he walked the long way home more hungry by the mile. Before we even get a chance to think about it, Jesus tells us while he was still far off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion; he ran and put his arms around his son and kissed him and instructs everyone, “Quickly, bring out a robe–the best one–and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. And get the fatted calf and kill it and let us eat and celebrate; for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!’” And they began to celebrate.”

Not the sort of welcome any of us expected, but before we have time to think about if this father’s welcome is overly generous or perhaps even unjust and rewarding of bad behavior, we are told of the reaction of the ever-dutiful, ever-responsible, elder brother. Remember him? Not everyone does. The one you may recall, who never left but remained by his fathers’ side the whole time, working. He exclaims, “Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours [notice he calls him ‘this son of yours’ not ‘my brother’] came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!” To be fair, we don’t know if the prostitutes part is true. The older brother may be embellishing, but it was at least what he imagined as he worked day after day in his fathers’ service while his younger brother was gone seeking God knows what. Where is the reward for being good? Where is the justice? Or at least the appreciation and recognition. The older brother was so angry that he refused to join the celebration, his soul full of righteous judgment and resentment. He may have even thought of the ancient prophet Jeremiah’s lament to God, “Why does the way of the guilty prosper? Why do all who are treacherous thrive?” (12:1). Or the prophet Habakkuk’s complaint to God, “Why do you look on the treacherous and are silent when the wicked swallow those more righteous than they?” (1:13). The elder son is the most understandable of the characters in the parable and he takes his place alongside the good and suffering righteous elsewhere in the Bible and in every century.

The character who makes no sense is the father. He’s the scandal. He’s who I suspect the story is really about, much like all other stories in the God-obsessed book otherwise known as the Bible. The Father accepts the risk, in granting the request and dividing the property, that property will be squandered. Parents get requests like this from time to time and know to say, “No, you can’t yet have the keys to the car!” This father, knowing full well what may happen, says, “Yes.” If we had a God like that, the world could look … well … exactly like our world, where people have choices often appearing to exceed their capacity to make them wisely.

In the same way, there is this inexplicable generosity of the Father in the parable who for no good reason, not only has mercy, but fully accepts his younger son back not as a hired hand, but as “a son.” Some people entertain themselves by coming up with theological questions that are hard to answer, but the most unanswerable theological question of all is why God loves any one of us in the first place? Jesus puts that love of God for us front and center in this parable as a kind of scandal. It is not explained or justified. It is simply there. Just as it is in the real world, really there inexplicably.

In so many books, a great deal is made of the human search for God. Christianity has things to say about that, but that is not what moves today’s parable forward. In this parable, it is the other way around. Notice that Jesus makes sure to tell us that while the prodigal is still far off, the Father sees him and goes to him. In fact, he ran and put his arms around him and kissed him. Likewise, when the older brother is angry and refuses to come in and celebrate, the father once again goes out to him in the same spirit as he welcomed his other son. In the world of the parable and in our world what matters is who this God is that we don’t quite understand and what he does for us.

Whatever one may have to say about the prodigal younger brother, by the end of the story, he knew what he had lost and what he had found. He learned it the hard way. The father says to the older brother, “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours.” Would the elder brother have appreciated his inheritance more if he had squandered it and spent his own time with the pigs? He didn’t see what he had and always had had.

The very destabilizing loves and desires that the younger son had such difficulty mastering were really what led him to feel himself finally loved by his father. His desires weren’t aimless when they were met by his father’s love for him. One of those most profound messages of the parable is its recognition that the persistent multiple desires of the human heart don’t necessarily doom us to restless wandering and endless searching. The reason is that, whether we have rebelled or not, there is an inexplicably generous heart that is the Source of all things, One that sees us and comes to us and loves us and invites us to the celebration before we ever realize that that is what we most truly want. The open question is when and how any of us will find our way to it?

We reenact the central dynamics of Jesus’ story every week here at this altar. Whatever your conflicted history of finding what you want in life, know that God, like the Father in Jesus’ story, was here before you were, inviting you first, whoever you are, wherever you are. No matter how many other things you have wanted in the past, no matter how much what you desired may have disappointed you, God, for some reason none of us will ever understand, runs out to greet you before you ever arrive at where you are going. You are welcome here today and you will be tomorrow and after that as well. Amen.