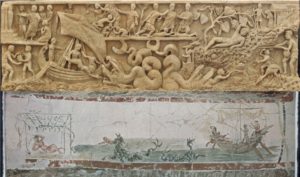

In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. We meet up with Jonah at the end of the book this morning and not at the more famous beginning where–running from God–he hurls himself off a boat at sea and is swallowed by a sea monster. After all that, God said to Jonah, “Is it right for you to be angry about the bush?” And Jonah replied, “Yes, angry enough to die.” Jonah was angry at the bush, really angry. To be fair, Jonah had had a really long week. The bush withering and letting him down was just one things too many. He had hit his limit. It is tempting to judge Jonah here and laugh at this comic scene of the man coming completely undone by a bush. Isn’t it? But in 2020 a lot of us have had days that are just one thing too many. There has just been too much disappointment and loss, already. The story of Jonah has had something to say generation after generation and 2020 is no different. From the earliest Christian centuries, we find ancient pictures of Jonah, see here is Jonah on the boat, Jonah being eaten by the sea monster (always drawn more like a dragon than a whale because their knowledge of whales wasn’t great), and Jonah sheltering under his bush.

Jonah was really upset because he had in his mind a pretty clear idea about the way things ought to happen. Ninevah was the capital city of the ancient Assyrian Empire. Ninevah was one of the first cities that realized it had the power of enslaving all of its neighbors simply by having the most powerful army. Jonah happened to be one of those neighboring peoples forcibly subjugated to this empire. Out of his deep faith in God, Jonah believed Justice would prevail and really wanted to live long enough to see Ninevah finally get what it deserved. He was waiting for the reckoning. Jonah is one of the good guys and a much-heralded prophet according to the Bible.

Jonah’s real problem was that God didn’t agree with Jonah’s plan, no matter how good it was. As the Bible tells its readers all the time, in the words of the Jonah’s fellow prophet Isaiah, “My thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways, says the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts” (55:8). Jonah was angry at the bush, but he was really disappointed and sad that God had failed to punish the Ninevites according to Jonah’s notion of what is right and wrong. As Jonah complained to God, Jonah explained how much he did not want to give the citizens of Ninevah even the opportunity to change their ways. He said, “I fled [because] … I knew that you are a gracious God and merciful, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and ready to relent from punishing.” It’s a hard story for any of us that happen to be too attached to what we think should happen in the world.

For those of us who really want our ways to be God’s ways and our thoughts to be God’s thoughts. Anger–like Jonah felt –is such a powerful emotion, that much of the time we don’t realize that it is really a kind of substitute emotion, or a kind of stand-in for something else that is underneath it that we don’t have to feel if we are angry enough. Usually, anger, in its own destructive and primitive way, is doing its best to protect us from disappointment, powerlessness, or sadness. Anger may protect us temporarily, but it doesn’t heal us.

Jesus may well have been thinking of Jonah when he tells the story of the landowner who early in the morning agrees to pay a group of workers a certain amount to work in his vineyard all day. A few hours later, he hires more workers to work the remainder of the day. He does the same again a few hours later and finally, with just about an hour left in the workday, he hires yet another group to work the final hour. At the end of the day, the landowner pays every worker the same amount, the amount that those who started earliest in the morning had agreed to. Of course, those who worked the longest cried unfair and were no longer happy with the amount they had earlier thought was just about right. Jesus’ landowner responds saying, “I chose to give to this last the same as I give to you. Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or are you envious because I am generous?” “Are you envious because I am generous?” Like Jonah, I’m sure they answered, “Yes.” And they had good reason to be angry. They worked from sun up to sun down and didn’t get any more than the ones that just worked the last hour.

Jesus’ landowner doesn’t feel obligated to explain anything. It could be that like most small business owners, he didn’t want to spend more than he had to, but needed to hire workers because the fruit needed to be harvested before it went bad. And as the day went on, it wasn’t clear that the job was going to get done, so it became worth it to pay whatever it took to get the fruit harvested, especially when they were still working that last hour. I can see the landowner– as that last hour approached–deciding to overpay because that was the only way to get the job done. But that explanation wouldn’t have helped those who labored all day.

“Unfair” is so powerful and feels so bad. It feels bad when we’re children on the playground, or when we’re adults in the workplace, or sitting next to Jonah, doing all the right things, while watching evil doers seemingly go unpunished, or not be able to hold our annual September “welcome back” picnic last Sunday at the church in the sunshine with the children running around giggling for no fault of our own. And God says, “Paul, you’re not angry about all that, are you?” It feels not fair.

There is the “unfair” we feel from other people’s action or inaction, but Jonah and Jesus’ parable are not really talking about that. The “unfair” they are talking about is–like nearly all the stories in the Bible–about God. They are talking about when you get past everything else that might be bothering you, and you get to the very Source of the universe, you get to the heart of the matter, and Jesus says there, “The last will be first, and the first will be last.”

It is good Jonah at the end of the book, really angry staring down his God, knowing that God was going to do whatever God was going to do. After three days in the belly of the sea monster, and more time in Ninevah with people he hated, and finally, alone hiding under a bush that feels like his only shelter from the bad mean world, the bush withers suddenly, and he is completely exposed and left with nothing but God. As readers, we travel so far with him and then we’re never told what he decides to do. Who does he decide to be? In the same way, Jesus doesn’t tell us what the disgruntled workers do when it’s time to show up for work again the next day? Of course, we’re not told, because both the stories are not about them. They are about us and the fundamental decision we make, over and over again, about who we are, in the world we have, in relationship to the Source of all of it, the God that is ultimately bigger than every one of our understandings (the understandings that we are so attached to, but are no more permanent than Jonah’s bush).

Jesus and Jonah offer us a connection to life that isn’t constrained by our constant need to explain everything and put everything in boxes labeled “good” and “bad,” “right” and “wrong.” At the end of his unhappy week, Jonah may well have laughed not knowing why, and put one foot in front of the other, not alone, but in the company of a God he didn’t understand at all. Because he finally saw that God was God and he was not, and that that is a perfectly fine way to make one’s way in a world where most things are beyond our control. He may well have felt a bit lighter, unburdened by the weight of his own convictions about the way things ought to be.

So may the God who always surpasses all our efforts to understand, who alone laid the foundation of the earth, whose wisdom far exceeds even our most thoughtful notions of justice and fairness, liberate us from the burden of our own thoughts, free us from all anger, and make us inwardly strong and able to face the challenges yet to come. Amen.

The Rev. Dr. Paul Kolbet